In the waters of the Arabian/Persian Gulf live dozens of shark and ray species – the elasmobranch branch of cartilaginous fishes. Many of them remain poorly studied, exposed to bycatch, targeted fishing, and habitat loss, which makes them rare or at risk. Gulf Elasmo Project documents the diversity, distribution, and conservation status of sharks and rays across the region. This feature highlights a top 10 of rare species – with field-ready photo prompts, plain-language descriptions, range notes, ecological roles, and the principal threats they face.

Why documenting rare species matters

Until recently, knowledge about elasmobranchs in the northwestern Indian Ocean – including the Arabian Sea, the Gulf and adjacent waters – was thin. Even today, absolute abundances recorded in independent surveys are low, especially on shallow, heavily used shelves. Low reproductive rates, high bycatch, and the degradation of coastal habitats create a perfect storm of risks. In this context, a clear, photo-oriented catalog is more than an educational resource – it is a conservation tool. Below are ten such species, in no particular order.

1. Arabian Carpetshark (Chiloscyllium arabicum)

- What to look for in photos: a small bamboo-type carpetshark with a cylindrical body, generally uniform sandy-brown to grayish upper side, minimal patterning, tiny barbels near the mouth, and a relatively short head. Adults rarely exceed 70–80 cm.

- Range & habitat: widespread but patchy along shallow Gulf coasts, often under 10 m. Favours coral rubble, mangrove edges, lagoons, and calm, turbid embayments.

- Ecological role: benthic mesopredator feeding on small bony fishes, shrimps, crabs, and mollusks. By rooting around in sediments it helps structure invertebrate communities.

- Threats & status: mostly vulnerable to gillnet and trawl bycatch on inshore flats. Slow growth and site fidelity make local declines likely. Regional assessments have flagged increasing pressure in nursery habitats.

- Why it’s “rare” to the public: small, nocturnal, and cryptic, so it is rarely photographed by casual divers compared with charismatic reef sharks.

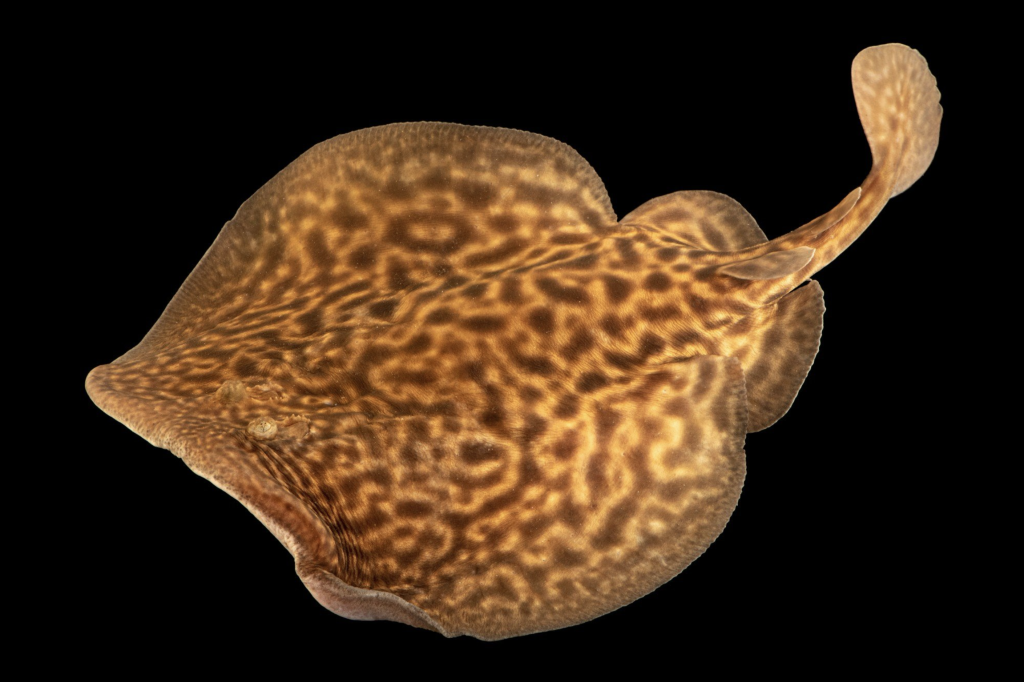

2. Persian Gulf Torpedo (Torpedo sinuspersici)

- What to look for in photos: a round electric ray with a near-circular disc and a short tail. Typical patterning shows a brown base with cream, meandering lines and fine spotting. Eyes are small and set close together.

- Range & habitat: northwestern Indian Ocean including the Gulf. Burying species of soft sands, outer lagoons, and the base of coral slopes, down to roughly 150 m.

- Ecological role: ambush predator on small fishes, using paired electric organs to stun prey. Often half-buried with only eyes visible.

- Threats & status: taxonomic uncertainty and a scattered record create a “data-poor” situation. Bottom trawls and demersal gillnets are the main risks.

- Why it’s notable: a visually distinctive endemic-leaning ray whose exact population boundaries are still being resolved, underlining the value of citizen-science photos with clear dorsal and ventral views.

3. Giant Guitarfish (Rhynchobatus djiddensis)

- What to look for in photos: a massive wedge-shaped ray with a shark-like tail and a long, guitar-like snout region. Dorsal surface usually gray to olive with pale ocelli or spots. Adults can approach 3 m total length.

- Range & habitat: western Indian Ocean including the Red Sea and the Gulf. Prefers sandy shelves, nearshore bars, and channels around reefs, often within 5–50 m.

- Ecological role: a top benthic predator among rays, crushing mollusks and crustaceans and maintaining healthy benthic assemblages.

- Threats & status: heavily impacted by targeted and incidental capture for high-value fins and meat. Extremely low reproductive output and late maturity push the species into the highest extinction risk categories in multiple regional listings.

- Field tip: when photographing, include a scale reference and dorsal markings near the shoulders – these can help separate it from look-alike wedgefishes.

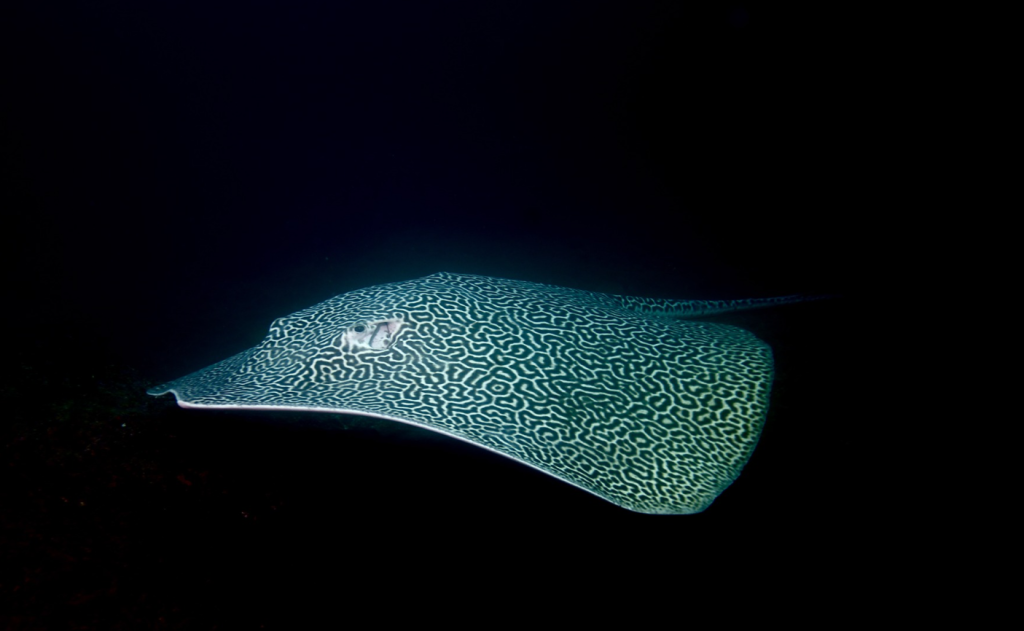

4. Honeycomb Stingray (Himantura uarnak)

- What to look for in photos: a broad, rhomboidal whipray with the iconic honeycomb or reticulated mesh pattern over a sand-colored background. Tail long, with one or more venomous spines.

- Range & habitat: Indo-West Pacific with records from the Gulf. Occupies lagoons, sandy flats, and seagrass edges, often in 1–20 m.

- Ecological role: a heavy-bodied bioturbator – its foraging pits oxygenate sediments and redistribute nutrients. Preys on crustaceans, bivalves, and small fishes.

- Threats & status: coastal fisheries, habitat loss in embayments, and targeted removal in areas of heavy human use. Because juveniles use shallow nurseries, shoreline modification has outsized impacts.

- Photo guidance: dorsal images that capture the pattern density from center to margins help with ID, as reticulated whiprays can be confused in the field.

5. Oman Cownose Ray (Rhinoptera jayakari)

- What to look for in photos: a schooling cownose ray with a broad, kite-like disc, distinct subrostral lobes, and a light brown top with pale underside. The head is subtly notched, giving a “split” rostrum appearance in frontal shots.

- Range & habitat: northwestern Indian Ocean including Omani and Gulf waters, typically over continental shelves and sandy corridors where mollusks are abundant.

- Ecological role: a mobile shellfish specialist whose herds can strongly influence clam and oyster beds, shaping benthic community turnover.

- Threats & status: vulnerable to net fisheries and coastal development. Schooling behavior makes it susceptible to episodic high mortalities when shoals intersect gear.

- Observation note: aerial or drone imagery during calm mornings often reveals migrating lines of cownose rays over bright sandy bottoms.

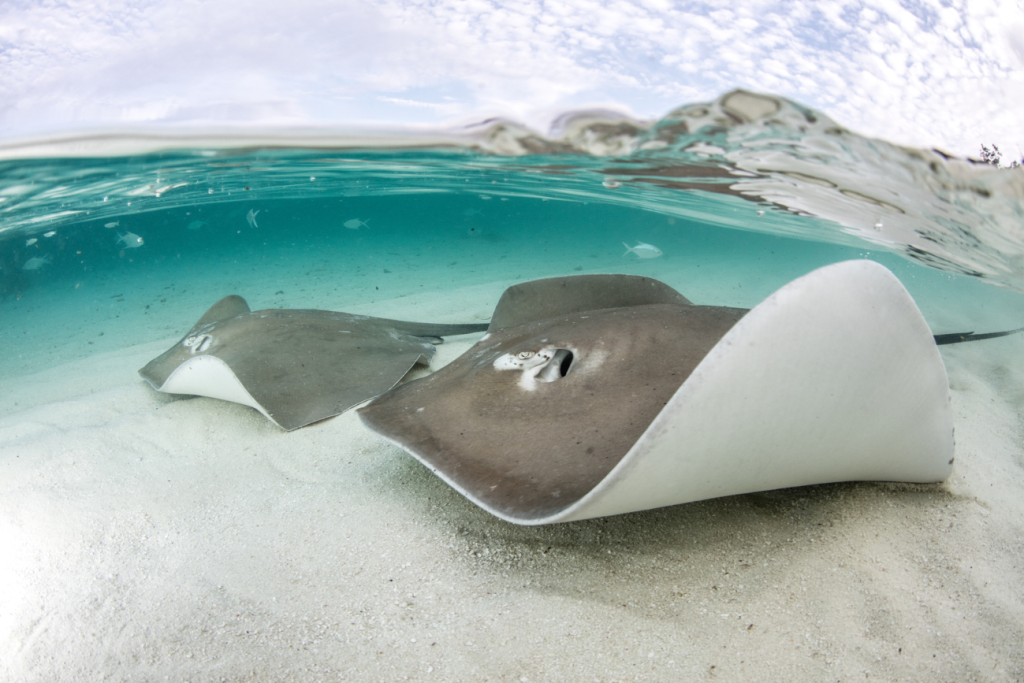

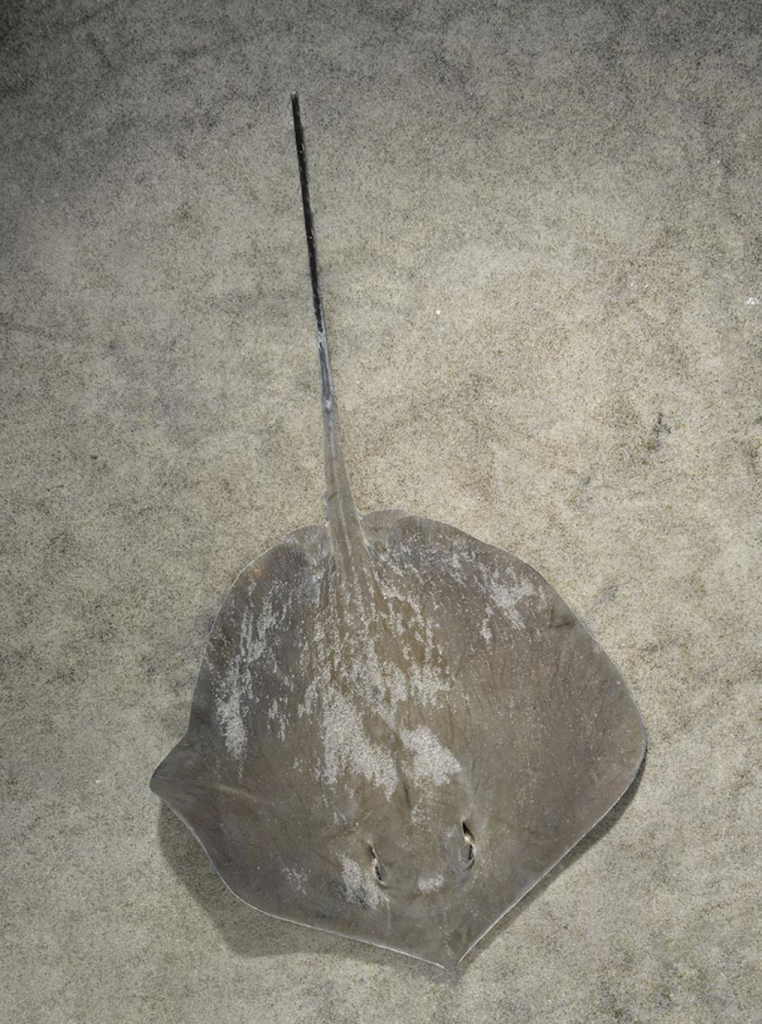

6. Cowtail Stingray (Pastinachus sephen)

- What to look for in photos: a large, almost circular disc with a very long, whip-like tail that lacks prominent dorsal fin folds. Dorsum gray-brown to olive, often uniform.

- Range & habitat: common historically on Gulf shallows, lagoon mouths, and open sand plains. Juveniles use sheltered coves and mangrove margins.

- Ecological role: powerful sediment mixer. By fanning and digging for prey, it keeps infaunal communities dynamic and helps recycle nutrients.

- Threats & status: inshore gillnets, shore seine activity, and loss of nursery habitats. Even modest increases in fishing effort can depress local age structure because of late maturity.

- Handling ethics: never lift a stingray by the spiracles or gill margins. If assisting researchers, support the disc with both hands and keep the tail directed away from people.

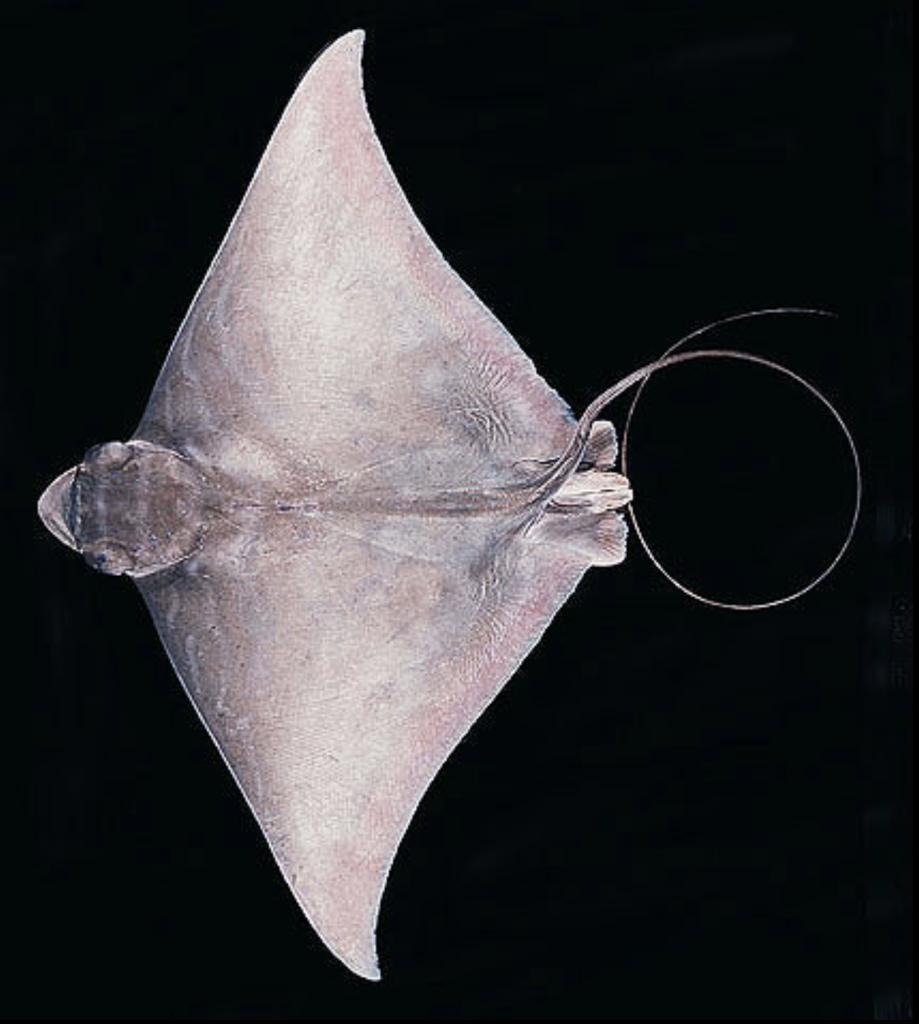

7. Banded Eagle Ray (Aetomylaeus nichofii)

- What to look for in photos: a graceful eagle ray with a long tail and bold transverse bands or paired rows of spots across the wings. The head is streamlined with a slightly projecting snout.

- Range & habitat: Indo-West Pacific with records into the Gulf. Uses open shelves, sandy gulfs, and occasionally estuarine mouths, often gliding well off the bottom.

- Ecological role: a mobile predator of hard-shelled invertebrates, capable of long movements that connect distant foraging grounds.

- Threats & status: taken as bycatch in trawls and set nets. Fragmented records and low encounter rates suggest local rarity in the Gulf.

- Photographing advice: oblique side-on shots that capture the full banding across both pectoral fins are ideal for confirming ID.

8. Slender Weasel Shark (Paragaleus longicaudatus)

- What to look for in photos: a small, sleek hemigaleid with a long caudal fin, narrow snout, and fine teeth suited to small fishes. Coloration is typically gray with a paler belly and subtle fin margins.

- Range & habitat: scattered records from the Gulf and adjacent coasts, usually on shallow continental shelves and turbid nearshore zones.

- Ecological role: a mesopredator linking small schooling fishes to larger sharks and marine mammals. Presence can indicate relatively intact shallow food webs.

- Threats & status: highly susceptible to inshore net fisheries. Because small sharks mature late compared with many teleosts, even low levels of chronic bycatch can cause declines.

- ID tip: clear lateral images of the caudal fin proportions and precaudal body length help distinguish it from other small gray sharks.

9. Arabian Whipray (Maculabatis randalli)

- What to look for in photos: a flat-bodied whipray with a very long, slim tail and a dusky to brown upper surface dotted or banded in subtle patterns. The snout is gently rounded.

- Range & habitat: Gulf-centered distribution with a strong association to shallow sand flats, estuaries, and reef lagoons.

- Ecological role: an important shallow-water bioturbator and a bellwether for nearshore habitat quality. Regular sightings can indicate healthy flats and seagrass edges.

- Threats & status: recently described relative to other rays and still under-documented. Local pressures include shore development, boat traffic in lagoons, and artisanal netting on tidal flats.

- Citizen-science note: dorsal photos with a visible tail base and any distinct banding are especially useful for confirming records.

10. Green Sawfish (Pristis zijsron)

- What to look for in photos: an unmistakable rostrum – the toothed “saw” – with numerous evenly spaced teeth, a robust, torpedo-like body, and a greenish-gray hue dorsally. Large dorsal fins sit far back on the body.

- Range & habitat: historically widespread in tropical Indo-West Pacific shallows, including the Gulf’s sandy embayments and estuarine mouths. Modern Gulf encounters are exceedingly rare and may be limited to historical records and occasional unverified reports.

- Ecological role: a unique apex benthic predator. The saw is used to stir and slash through schools and to excavate benthic prey, shaping community structure in soft sediments.

- Threats & status: one of the most endangered elasmobranchs globally. Nets of almost any mesh entangle the rostrum. Habitat loss in deltas and lagoon systems further reduces recruitment.

- Conservation message: any credible sighting merits rapid documentation with location, date, approximate size, and – if safe and legal – clear photos from multiple angles.

Field guide add-ons for each species

To help readers collect useful, conservation-grade observations, here’s a repeatable mini-template you can embed under each species card:

- Photo checklist: dorsal overview – close-up of distinctive markings – side profile showing fin shapes – tail base and any spines – if safe, a gentle scale reference (fin, slate, or ruler)

- Habitat note: depth, bottom type, water clarity, presence of seagrass or reef rubble

- Behavior: resting, cruising, schooling, feeding pits, courtship, nursery aggregation

- Human context: nearby gear types seen (traps, gillnets, trawlers), boat traffic, tourism intensity

- Data to log: date, time, coordinates, estimated size, number of individuals, photo filenames

Conservation landscape in the Gulf – what the patterns suggest

- Coastal squeeze: many of the species above rely on shallow nurseries and sand flats that are also prime zones for coastal development. Reclamation, dredging, and hardening of shorelines compress usable habitat.

- Bycatch gravity: even where target fisheries are modest, nets and trawls exert constant pressure on rays and small sharks. Rare species become rarer first because their life histories offer little buffer.

- Knowledge gaps: taxonomic uncertainties and sparse ID-quality photos can mask declines. The difference between a “rare but stable” and a “crashing” population often hinges on whether observers can generate verifiable records.

- Why photos matter: repeatable, geotagged imagery lets scientists map hotspots, time nursery use, and refine ID keys. For patterned rays especially, dorsal pattern libraries can support mark-recapture style estimates.

How Gulf Elasmo Project readers can help

- Report sightings: log date, coordinates, depth, habitat, approximate size, and behavior. Attach your best two or three photos that clearly show diagnostic traits.

- Prioritize ethics: maintain distance, never chase or corner animals, and avoid flash in very shallow water at night. For stingrays, give the tail a wide berth.

- Note context: if fishing activity or abandoned gear is present, add a short line in your report. Such metadata helps interpret risks.

- Share responsibly: when posting on social media, remove precise coordinates for extremely rare species like sawfishes. Send full details privately to conservation teams.

Closing thoughts – a forward look

This catalog is only a snapshot of the Gulf’s elasmobranch diversity. It centers on species that are rare in public awareness and, in many cases, scarce in surveys. Some are cryptic specialists of mangrove-lagoon mosaics, others are wide-ranging cruisers of open shelves. What unites them is their vulnerability to cumulative coastal impacts. The path forward is clear: better documentation, smarter habitat protection, and practical, gear-aware fisheries management. With consistent, well-annotated photos and site notes from divers, anglers, and coastal visitors, Gulf Elasmo Project can sharpen species maps, refine risk assessments, and help local authorities focus protection where it matters most.

Summary cards – quick reference for editors

- Focus: rare and lesser-known sharks and rays of the Arabian/Persian Gulf

- Value: niche, region-specific content that is underrepresented online, high potential for organic traffic from long-tail searches

- Structure: 10 species with photo cues, range, ecological role, threats, and tips for documentation

- Tone: practical, field-oriented, conservation-minded

- Brand: “Prepared with input from Gulf Elasmo Project” woven throughout

Useful Links:

How to Participate in Gulf Elasmo Project Research

A Guide to the Underwater Wonders of the Persian Gulf

Why Sharks Matter for the Arabian Sea Ecosystem

A Human’s Guide to Sharks of the Arabian Gulf